- Home

- Bajoria, Paul

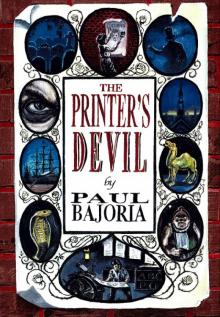

Printer's Devil (9780316167826)

Printer's Devil (9780316167826) Read online

Copyright

Copyright © 2005 by Paul Bajoria

All rights reserved. Except as permitted under the U.S. Copyright Act of 1976, no part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, or stored in a database or retrieval system, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

Little, Brown and Company

Hachette Book Group

237 Park Avenue

New York, NY 10017

Visit our website at www.HachetteBookGroup.com.

www.twitter.com/littlebrown

First eBook Edition: October 2009

ISBN: 978-0-316-08910-4

The characters and events portrayed in this book are fictitious. Any similarity to real persons, living or dead, is coincidental and not intended by the author.

Endpaper photograph copyright © Picture Collection, The Branch Libraries, The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations

To Mum and Dad

with infinite love and thanks

Contents

Copyright

1 THE CONVICT

2 INDIAN INK

3 THE SWORD

4 THE SUN OF CALCUTTA

5 THE BOSUN’S BOY

6 CAMEL-HUNTING

7 FLOUR AND ASHES

8 ENCHANTED MUSIC

9 HIS LORDSHIP

10 THE MAN FROM CALCUTTA MOVES FAST

11 THE PAPERMAKER

12 DARKNESS FALLS

13 THE LURK

14 DEATH I

15 DEATH II

A Preview of THE GOD OF MISCHIEF

1 A BURIAL

1

THE CONVICT

He was the ugliest, most evil-looking man I’d ever seen.

He glared up at me from the poster, his outline glistening as the ink dried, making him seem more alive and threatening. I held him out at arm’s length to stop him from creasing.

COCKBURN

I scanned his name, mouthing it as I assessed the big black letters. Were they straight enough? The top part of the “R” hadn’t quite come out properly. Nevertheless, the effect was striking; and, although I felt slightly afraid of the vile-eyed villain, who seemed to strain to clamber out of the picture and throttle me, I was quite proud of my handiwork. After all, I told myself, if the poster scared people they’d be all the more likely to try to help catch him.

The exclamation point, I noticed, was a bit lopsided. I’d have to go back and straighten the type before I did any more.

COCKBURN

ESCAPED

from our NEW PRISON at CLERKENWELL, the 14th day of MAY.

The Public is ADVISED that this Man IS VERY

DANGEROUS!

Being a printer’s boy was hard work. I had to run errands, and do all the boring and dirty jobs, and Mr. Cramplock only paid me a couple of shillings a week, which wasn’t much. But the good part of it was that our shop was the first place people came when they had any information to pass on, so Cramplock and I found out about it before anybody else. We were always making posters and handbills and books and newspapers, informing people of what was going on in the world. If there was any meeting called, or play to be performed, or auction to be held, or curious object to be displayed, or items stolen, or convicts escaped, or persons to be hanged, or corpses found drowned, or loved ones gone missing, chances were we’d know about it. It used to make me feel quietly important, walking through the streets of London and repeatedly seeing the huge inky letters of my own posters plastered across brick walls and wooden fences. They made people happy, and curious, and afraid; they made people talk. It felt as though things happened because of what I did.

The printer’s devil, they used to call me. I had short black hair and a dirty face, usually, because of all the ink that got splashed around everywhere in the workshop; underneath the ink my skin was brown from the summer sun. I was rake-thin, in those days, and I usually worked in long breeches which didn’t fit very well round my waist so I had to keep hitching them up, especially when I was running. “Here comes the printer’s devil,” people would say. At first I used to think it wasn’t a very nice thing to call someone, but no one seemed to mean any malice by it, and I soon got used to it.

“Secure that exclamation-mark, Mog,” Cramplock said, appearing at my side and surveying the poster.

“Don’t he look mean, Mr. Cramplock?” I said, rather admiringly, as I held up the big poster again.

“Murderous, Mog, mmm. Mur — derous!” He repeated the word with some relish, peering over his spectacles approvingly.

“What did he do, Mr. Cramplock? Did he murder someone?” I asked eagerly. I was hoping fervently that he had, until it occurred to me I probably shouldn’t be hoping such things.

“I don’t know, Mog. Best not to take a chance, though, eh?”

“IS VERY DANGEROUS!” I read again, before laying the poster aside. As I placed it on the table, the paper bent slightly in the middle, so the convict seemed to be leaning forward deliberately to menace me with his broad, clenched face. His eyes, although quite small, like unwelcome little black blemishes on the paper, were by far the most prominent feature of his face; and they held me with a vicious stare. I’d never forget this face, I told myself, nor that name etched in heavy letters by chunks of black iron pushed into the coarse white paper.

“Cock,” I said slowly, “Burn.” And the eyes of the escaped convict flashed, as if in recognition of his name; as if there were indeed something burning behind them, a kind of sinister flame.

Almost expecting to see him creeping up on us from behind, I looked around the shop nervously. “You don’t suppose he’s hiding near here, do you, Mr. Cramplock?”

Cramplock laughed shortly. “If he’s got any sense, he’ll have fled a lot farther off than this.”

He turned away, tugging at the grubby collar of his shirt to let some cool air inside. It was the hottest week of the year so far: in fact, we were having the hottest weather I could remember in my entire life, and working the presses was hard and sticky work, so that our shirts were damp and both our faces glistened with sweat as we worked. Cramplock rubbed his cheekbone just beneath the rim of his glasses with an inky finger, a habit he’d had for as long as I’d known him. He always had a smear of printer’s ink on his cheek, like a bruise; and today when he rubbed his face, his finger came away wet.

“Phew … it’s hot work again today,” he said, breathing heavily. “Only May, and look at it. If it keeps this up, we’re in for quite a summer. Even though we’ve got Winter inside. Eh?”

It was a joke. He used to make it quite frequently, in one form or another. My name, you see, is Winter. Mog Winter. People sometimes said it was a peculiar name to have, but it’s always suited me fine. Sometimes in the print shop when there was nothing else to do, I used to make up a form with just my name in, and print my name on old scraps of paper. Sometimes I used three big capitals, M O G, sometimes a capital and two lower-case ones, Mog, and sometimes I’d bring out the fancy type which made the letters look as though they were written with a quill-pen rather than printed. Mog. I used to stare at my name on the paper for ages. After a while, it didn’t seem like my name at all: it was as though I’d never seen it before, the letters just meaningless marks which didn’t spell anything. I had quite a collection of these various Mogs by now: Cramplock probably wouldn’t have been very pleased if he’d found out I was using up paper like this, but I somehow couldn’t bring myself to throw them away.

I wasn’t going to have time for such idle pursuits tonight because I knew that before I went to bed I had to make a hundred copies of the Cockburn poster. I was about to ink up again when Cram

plock came over.

“Before you do that, Mog, how about fetching us something to eat from the Doll’s Head?”

I nodded, relieved, because my stomach was beginning to rumble like an old cart. It was nearly six o’clock and the shop was closed to customers, but he’d wanted to keep going until we’d finished these posters and something else he was preparing for a man in the theatre.

The theatre bills were his favorite job: he used to lavish hours of painstaking attention on their different-shaped letters and colored inks, making them seem as cramped and exciting as the theatre itself. “From Brighton, the Celebrated Mr. Symington! Flying Through the Air, Without Visible Means of Support, the Sunderclouds! And Presenting for the First Time in London, the Remarkable Mrs. Victor Reed (who Executes a Genuine Faint in the Role of Lady MacBeth!)”

I left him working the noisy press and darted towards the door before he had time to change his mind. The thought of meat and ale was making my mouth water already. I seemed to be hungry absolutely all the time at the moment. It might have been because I used to share whatever I had to eat with my dog, Lash, and most days he used to get the better of the meal. Lash was the most adorable living creature I ever met, even counting human beings. He was all sorts of dog and no sort of dog, probably five or six breeds rolled into one, with quite a lot of spaniel in him and a bit of lurcher. He was called Lash because he had great big eyelashes — and when he looked at me from underneath them, I could willingly give him every last morsel of food I possessed, however hungry I was.

As I was about to leave the shop I gave a short whistle; footsteps clattered down the wooden stairs, and there was Lash by my side, licking my inky fingers and tickling my wrists with his whiskers, and wagging his tail so hard against the panels of the wall when I said the word “Dinner” that it sounded like someone beating out a rhythm on a barrel. Lash and I went everywhere together. We were well known in Clerkenwell and, I suppose, pretty well known everywhere else. So we emerged into the evening air together, in such a hurry that I forgot my cap.

The empty windows of the house next door stared down at me as we went by. It had once been a grand town house, but it had been deserted now for many years, after being burnt out in a terrible fire. Inside, the fire damage was still there to be seen: blackened walls, the floor covered in ash and chunks of charred wood, the window-frames burnt to a crisp, the glass in the windows opaque with smuts. The humble, grey little building which was now Cramplock’s shop, built right up against it, must once have seemed like an insulting excrescence bubbling out of its towering northern wall; but the printing shop had remained in use all this time, while its haughty neighbor had been left to rot. With some other children, I’d broken in once: but we hadn’t stayed for long: there were too many rats, and every step caused a creak or a groan which made it seem as though the whole house was about to collapse on top of us. No one could explain why it hadn’t been knocked down years ago; and its charred black facade, like a sightless face, often made me shudder as I stepped over the garbage in the lane.

I should explain that, by that summer when I was twelve, when all the things happened that I’m going to tell you about, I was very well used to looking after myself. I never had a mother and father looking after me, and I don’t really know much about what happened to them, except that my Ma died in a big ship on a voyage from India, from the effort of giving birth to me, and I had to live in an orphanage for the first few years of my life. I don’t know much more. Since I ran away from the orphanage I’d worked for Cramplock, and in return for a chunk of the wages he paid me he let me sleep in an upstairs room in the printing shop. It wasn’t very big or very comfortable, but it had most of what I needed — a bed for me and a basket for Lash, a table and a jug of water for washing, and a little cupboard for my things — and it was the closest thing to a home I’d ever had.

If it weren’t for Cramplock I don’t really know what I’d have done. Become a thief, maybe, like lots of the other kids who grew up around here. A couple of streets away lay the massive prison with its high wall, behind which someone else would disappear every so often when they’d been caught stealing or doing something wicked. People would gather to watch the big iron gates swing open, admit the cart, then close. No one ever seemed to come out. They said the only way out of the jail was to be carried out in a box. They died in there. I used to be able to see the men burying them in the fields outside.

But, just occasionally, one of them found a quicker way out.

I nipped through the alleyways, with Lash getting in the way at my ankles. The late spring sky was a deep heat-soaked blue above us, but in some places it seemed like nighttime, because the houses on either side of the lanes leaned inwards at the top until they almost touched, so the sunlight could hardly get through. To get to the Doll’s Head we had to go past Cow Cross, where there was always a lot of dirt lying around from the cattle which were driven through there twice a day. If the presses weren’t making a noise, Cramplock and I could often hear their mooing protests in the morning and afternoon as they clomped through the streets getting in the way of the traffic. It was always smelly at Cow Cross, and if it was raining you could hardly move for the dirt, trodden into a paste a foot thick by the cows’ hooves. Still, I preferred that to the smell of the Fleet, which ran between the backs of the nearby houses. People said it used to be a river, once upon a time, when you could see the green fields from the back windows of the houses there. But you wouldn’t call the Fleet a river now: it was more a sort of sticky black ditch which little kids used to get scolded for going near, on account of the dirt and all the rats. Especially during the summer, when you had to breathe through your mouth if you were anywhere near it, so as not to catch the smell. The cows didn’t smell half as bad as that — and since it was mainly people’s filth which made the Fleet stink, the only conclusion I could come to was that people smell a good deal worse than cattle.

And here was the Doll’s Head, with its big wooden pole propping up the top of the house to stop it from toppling into the street. You had to duck under the pole to get in through a little door, whereupon you found yourself in a tiny taproom, all higgledy-piggledy, as though it had been built by a man whose eyes looked in two different directions.

There was nobody in the room this evening — except Tassie, the landlady, of course. Lash gave a good-natured whimper of recognition when he spotted her plump face behind the bar.

“Tassie,” I said, “Cramplock’s hungry, and so’s Lash, and so am I.”

“Tell me when you’s never not hungry, Maaster Mog,” Tassie said, reaching over the bar to wipe a smudge of ink off my face with her fat thumb. The Doll’s Head had been built a very long time ago — in Queen Elizabeth’s time, someone said — and I suppose I assumed that Tassie had been there ever since then. She was usually cheerful, except on very wet days when the rainwater used to leak down through the timbers of the house and drip onto the back of her neck from a crack just above where she stood. She always called me “Maaster Mog,” and when she was cross with me she elongated it even more, so it came out as “Maaaaaster Moooooog.” I used to slink about and keep out of her way on those days. But usually she made me into quite an attraction if there was anyone else in the room: she’d tell them, “Well just look who it is, it’s Maaster Mog,” and she might come over and blow the dust out of my hair and rub my face just like she did today, and she’d say, “He’s one of my regulars, ain’t you, Maaster Mog?” and she’d laugh heartily at it as though she’d just told a good joke or sung a particularly fine song.

“What can you spare us to eat, Tassie?” I asked her, “along with your middling ale?”

She put her tongue in her cheek, which made it a good deal plumper than it already was. “Well now,” she said, “provided you can show me the right connidge” — she meant money — “what if I was to tell you there’s a big pink ham under my larder table?”

Lash reacted before I did, with a gruff woof of approval.

> “I’d say,” I said, “that ham would do nice. And bread would do nice, too.”

“What if I was to tell you,” she said, “there’s floury bread an’ all? And what if I was to tell you there’s ham and bread both, Maaster Mog?”

My eyes shone at her over the bar and she roared with laughter. “Don’t that make your eyes shine, Maaster Mog?” she said; and, as if she were talking to someone else, “just look at the lad’s big handsome eyes, me making his face light up like an angel’s face, I declare. You’ve got such eyes as a woman would die for, Maaster Mog, that you has. ‘Taint fair that a young man should have such eyes, when there’s ladies young and old would die for eyes that big and lovely.” I was quite used to hearing this, because she said it virtually every time I went to see her and, although I always made faces pretending I was bored of her compliments, I actually liked it. This piece of flattery about my eyes was nearly always followed up by another comment which she obviously thought rather clever; and, sure enough, she trotted it out again today. “Printer’s devil, they calls you,” she said, “but sometimes I have a hard time deciding if you’re devil or angel, Maaster Mog. Devil or angel!” And she went off into the back room, chuckling, to get the food.

I sat down to wait, and Lash spread himself out under a table. I watched Tassie moving briskly about behind the two great big polished pump handles where she pulled the beer. She always kept a cloth by them so that, whenever they got too grubby from all that pulling, she could wipe them down and they’d be as shiny as ever. “The shiniest taaps in Clerkenwell,” she always claimed, “and if you can show me shinier in all London, well I’d like to see ’em. See your face in ’em, you can, and it’ll never be otherwise, not while I’m on this good earth.” You certainly could see your face in them, but they were such a funny shape that when you looked in them your face appeared extraordinarily long and bendy, as if someone had taken you by the topmost hairs on your head and yanked until you were stretched out like a piece of dough.

Printer's Devil (9780316167826)

Printer's Devil (9780316167826)