- Home

- Bajoria, Paul

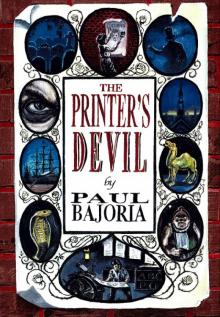

Printer's Devil (9780316167826) Page 16

Printer's Devil (9780316167826) Read online

Page 16

“Oh, I don’t think he finds much business anymore. A few of the poorer printing shops, and a newssheet or two, I suppose.”

“But not — official things?” I asked. “Not — the Customs House, or anyone like that?”

“Certainly not,” Cramplock said, “they only use His Majesty’s Stationer, and a royal watermark reserved for official documents.” He saw me looking at him intently. “So are you going to tell me what all this is about?”

“Oh — nothing special, Mr. Cramplock,” I said.

10

THE MAN FROM CALCUTTA

MOVES FAST

I was more worried than ever about Nick. If the bosun was in so much danger, then Nick was too — and now the man from Calcutta really had killed somebody.

I’d arranged to meet him after work at the fountain, but very late in the afternoon Cramplock insisted that we clean a whole lot of type particularly thoroughly and, after messing about with spirit and cloths and waste paper, I was at least an hour later in getting away than I’d intended. My cuffs stank of spirit, and I couldn’t get rid of the oily sensation on my hands, no matter how much I rubbed them, or how much Lash licked them. I kept having to stop him because I was sure it wouldn’t do him any good.

When we arrived, a clock was already chiming eight. It was still hot, but the shadows were growing long and the number of people was diminishing. I lurked on the street corner, watching, trying to catch a glimpse of Nick and yet stay out of sight until I could be sure there was nobody with him.

But there was no sign of him. Maybe he’d gotten tired of waiting, and gone home. Or maybe he hadn’t turned up at all. I waited for a while, and then decided to ask someone. There was an old woman sitting by the fountain, surrounded by black skirts, with a shock of red hair billowing up from her head which made her look rather like a volcano. She was selling flowers, and I’d watched her sitting chatting to passersby, and smelling her flowers when there was no one to talk to.

“Excuse me,” I said, “have you seen a young lad who looks a bit like me? In the last hour or so?”

“I see all sorts,” she told me, “from sittin’ ‘ere. Soldiers, I seen. Cattle, I seen. Men with pitchforks, men with bottles, men with carts. Boys I seen too.” She reached down for a flower and put it to her nose. I waited for her to speak again; but she seemed so engrossed in the flower, I eventually decided she wasn’t going to, without prompting.

“So?” I said, “did you see a lad or not? A bit taller than me, sort of skinny, with a big bruise up here.”

She was smiling at me from behind her flower. “Boys,” she said, “all shapes and sizes, some little, some fat, some blond, some black. Warious,” she mused, “as warious as flars. A man I seen with no legs today, swingin’ himself about on his fists. A grand man I seen with a wig as long as a horse tail. A man I seen with a big basket. A man I seen kickin’ a child, today,” she said, tailing off sadly and putting her nose back into the flower.

“Just a minute,” I said, “Lash, come here! Did you say a man with a big basket?”

Her eyes were twinkling, but she said nothing. I tied Lash’s lead to his collar, wary now.

“Where was he going? This man with a basket? Did he have brown skin? Or a mustache, or anything at all?”

Still her eyes twinkled.

“You buy a flar off me,” she said, suddenly and sweetly, “and maybe I tell you, mmmm?”

“Oh lor,” I said, “just a minute.” I fished in my pocket and found a halfpenny. “How many flowers do I get for this?” And how much information, I wondered.

“Roses,” she said, “tulips and roses. And lupins.” She looked up at me. “And white poppies,” she added, “Norfolk white poppies. You give me your ha’pney, and here’s half a dozen. Lovely Norfolk white poppies!”

I gave her the money. “Now,” I said, “this man with a basket.”

“Running,” she remembered, “not half an hour ago, as I sat here, running thataway. Yes — a foreign gentleman all right. ‘Andsome, and tall, and his coat black and beautiful. But a nervous gentleman, clutchin’ his basket, oh so precious! What was in it? Don’t ask me, but precious! Must a been! Thataway,” she said again, nodding over to her left, “running.”

“And the boy I was asking after?” I said. She shook her head, and went back to the flowers.

So the man from Calcutta’s trail had grown warm again suddenly. My mother’s face came into my head again, imploring as she had done in my dream this morning, clutching at her wrist. I had to go after him. The way the flower woman had indicated the man had gone was the same direction as Nick’s. I might as well head for Lion’s Mane Court.

When I got there I left Lash tied to the same post as before, promising him I wouldn’t be long. He licked my face trustingly, and I stood up. There was no sound from the bosun’s house as I crept through the passageway into the little courtyard, already bristling with shadow as the dusk closed in. There were no lights burning in the windows; but I thought I’d better watch for a few minutes to make sure the coast was clear — so, as before, I crept into the stable which belonged to the inn next door, and which afforded such a good view of the yard.

The dark corner where I wanted to sit was already occupied. By a familiar, pale object more than half my height, tapering inward toward the ground. The snake basket.

I stood frozen behind the stall, fervently hoping the horse wasn’t going to kick me. There didn’t seem to be anyone else here — just the basket, standing there like a silent oriental sculpture. The sun had now gone down completely and there wasn’t enough light here in the stable to see inside the basket, even if I had dared to lift the lid. But if I knew the man from Calcutta, he wouldn’t have left his precious snake in the basket unattended. The snake must be somewhere else.

And even as I stood there, in the damp corner of the stable, I began to detect from the darkness outside the sound of a low, sinuous voice … singing.

Sure enough, a peep through the hole in the stable wall revealed the dark, hunched figure of the man from Calcutta, over in the shadows, bending over the cellar grating.

He must have sent the snake inside.

I SHOW HIM DEATH SOON.

I was gripped by panic. Nick! I pictured him backed against the wall, terrified, as the snake reared its head, coiled at his feet or on his bed, its tongue flicking in the dank air. Agitated, in the dark, I lost my footing in the straw and reached out to grab something to steady myself. My hands clutched at the basket; but it couldn’t stop my falling weight and suddenly I was sprawling on the muddy straw. With a terrific clatter the box toppled over against the wooden wall, making the sick horse stir in its stall and give a kind of groan, which seemed to linger and resonate in the timbers of the stable until it was inconceivable that the man from Calcutta hadn’t heard it. Cursing myself for my clumsiness, I leaped back up to press my eye to the hole. I could see him looking over at the stable in alarm. He stood up, and began to approach.

I was trapped. He was coming back to the stable door, and there was no other way out! My only chance was to try and hide in the horse’s stall, at the back, in the deepest of shadows, and hope I wouldn’t be seen. I shuffled alongside the horse, patting the poor creature’s mangy flank and whispering, “Easy boy”

The stable door rattled. The man from Calcutta was standing, listening now, just a few feet away, just inside. I couldn’t see him; I couldn’t hear him; but I could sense him, his dark silent presence, between me and freedom. I prayed the horse’s wheezing breath would drown mine out, as I sank to my knees in an attempt to get as far out of sight as possible. Now I was kneeling underneath the horse: as I peered out between its trembling black legs, its grimy tail formed a kind of curtain between me and discovery.

I didn’t dare move. It was almost too dark to see anything at all, but now I could hear movement in the stable, and the man’s low murmuring in his own language. I realized my knees were getting wet, and a foul smell was rising to my nostrils as I crouched there. It

was all I could do to stop myself from coughing.

He stayed for about two minutes, I suppose — but it seemed like hours. Then there was the tiniest creak as he left the stable, and all of a sudden the sense of him was no longer there. Although I could tell he’d gone, I gave him plenty of time to get away. Just as I’d decided to risk crawling gingerly out of my hiding place, the horse gave a sudden shudder and a jet of something wet began to spray across my back.

I scrambled out and, as I stood up, I banged my head on a beam and doubled up again in pain. What a mess, I thought, clutching my head and feeling the stinking liquid dribbling down my shirt and pants. Why on earth had I let myself get mixed up in all this?

The basket had gone. The courtyard was empty, and the coast was clear. I scuttled across to the cellar window. A few times I hissed, “Nick!” — but there was no reply. Nothing stirred. There was no light.

I had to find out if Nick was safe. I’d have to risk going down into the cellar, through the scullery. I froze as the pink-painted door scraped across the floor when I pushed it ajar; but all seemed silent and still inside; and as I ventured in I saw no one on guard, and nothing blocking the trapdoor down to Nick’s little cellar room. Picking a lantern off a hook just inside the door, I ventured over to the trapdoor, pulled it up, and peered into the hole.

“Nick!” I whispered.

Nothing. Of course, I knew he wasn’t in there. They would never have left him unguarded with the cellar open like this. But I had to be sure. I took a couple of tentative steps down the ladder.

“Nick!” I squeaked. “It’s me!”

Still no sound. As the lantern sent its dim glow around the cellar, it was quite clear there was no one there.

So where was he?

I slid down the last two steps until I was standing on the grubby floor. I’d brought the most revolting smell into the cellar with me, and as I looked down I noticed I’d left little pools around my feet and some strands of yellow straw scattered loosely around the floor. I was very wary in case the man from Calcutta had left his snake down here, and for the first few minutes I just paced, slowly, around the little room, watching and listening for any sign of movement. There was nothing: it was soon clear that the man must have retrieved his snake before he left, having found no one here for it to bite.

Nor were there any clues as to where Nick might have gone: no notes, no sign of a disturbance. There was a low bed in a corner, and a small bare table in the middle of the room, with a flickering stub of candle on it in a waxy old dish. The only thing I discovered was a crumpled handkerchief, sitting on the old bedsheet, spotted with dark blood. What was the story behind this, I wondered with a sudden misgiving.

But all further thought was halted as I heard voices up in the courtyard, one of them unmistakably Mrs. Muggerage’s.

I was trapped! I suddenly realized I’d left the scullery door open, and I wouldn’t even have time to pull the trapdoor shut above my head. It was a dead giveaway. Thinking quickly, I threw a few things into disarray: ruffled up the bedsheet, tipped up the candle, flung open the cupboard, overturned a couple of bottles; then snuffed out the light and dived under the rickety old bed.

There was an almighty clattering from up above; and, almost as soon as I’d hidden myself, a shaft of light broke into the room and Mrs. Muggerage’s voice blared, “All right, come out, oo’ever you are! We’ve caughtcha!”

There was silence for a couple of seconds.

“Get down there and see who it is,” she said. And Nick’s voice piped up.

“But what if they —”

“Shut up and get down there!” There was a sudden series of thuds as someone half fell, half ran down the steps.

“There’s nobody here.”

“What?” Mrs. Muggerage sounded contemptuous, as usual.

“It’s empty,” said Nick’s voice, “there’s nobody here.”

I held my breath as Nick’s feet came close to the bed.

“Someone’s been here, looking for something. But they’ve gone.”

There was a clomping sound as Mrs. Muggerage came down to see for herself. Eventually I heard her grunt with disappointment.

“Well,” she said, “you can stay down ‘ere now. I’m going to put the keg back and if I hears one peep out o’ you …” Her threat remained unspoken.

The trapdoor was slammed and I heard Nick sigh. There was a creak as he sat on the bed; and then came the sound of the heavy keg being scraped back into place on top of the trapdoor. Nick began to sniff. At first I thought he’d detected the smell of the horse manure I was covered in; but I soon realized he was crying. I lay there listening to him, not daring to move.

Eventually I whispered, “Nick!”

There was a creak as he sat up, startled.

“Nick, it’s Mog,” I hissed, “I’m under the bed. Ssssh!” Trying to be as quiet as possible, I shuffled out, and sat up on the floor, blinking.

“Mog! What are you doing here? Why did you —“

“Listen,” I said, “the man from Calcutta’s been here. I watched him letting his snake into this cellar. He was after you, Nick, or somebody in this house anyway.” I got up and sat on the bed, so I didn’t have to whisper so loud. “He’s only just left,” I said, “two minutes earlier and you’d have disturbed him.”

“Mog,” Nick said, still sniffing, “you stink. Again!”

“I know, I had to hide under a horse. Where’ve you been?”

“It’s a long story.” Nick wiped his nose on his sleeve, and then his eyes. “How are you going to get out of here now?”

I hadn’t thought of this, I’d been so relieved to find Nick was all right; but I was more impatient to hear his story than to worry about how we might escape.

“Can Mrs. Muggerage hear us?” I asked.

“Not if we whisper.”

I decided I’d better try and start from the beginning. I told him about the snakebite; about the house next door to Cramplock’s; about the elephant statue and the cubbyhole; about the man from Calcutta’s latest note.

“He’s got it in for your Pa,” I said. “I’ve been thinking about that other note he left. And I’m pretty sure when he wrote ‘I show him death soon,’ he really meant the bosun.”

A sudden noise from above made us both jump; I stopped talking abruptly and we listened; but it seemed it was only Mrs. Muggerage slamming a door somewhere.

“I thought it was my Pa coming in,” said Nick. “He was so angry when he came home last night — mainly about you. He thinks you’re a spy for Coben. He kept asking me about you and I told him you were a saddlemaker’s boy called Jake. He beat me black and blue, Mog, I thought he was going to kill me.” He wiped his eyes again. “He didn’t believe a word I said. Oh, I hate my Pa, Mog! I hate him so much!”

Nick sounded as though he was about to cry again. I remembered what he’d said the other day, when I’d first met him, about my being better off than he was, despite not having parents at all. At first I’d thought he’d be anxious to learn his Pa was in so much danger; but now I was beginning to realize just what it might be like having someone like the bosun for a father.

He was silent for a few moments, swallowing his tears.

“So, where’ve you been?” I asked eventually.

“Ma Muggerage told him how I kept sneaking out,” he continued, wiping his nose, “and this evening he came bursting in and said if I was so good at crawling through windows I could come and help him. He took me to this little house where he said Coben had been living. I suppose it must have been Jiggs’s house, you know, where they took you and locked you up the other day. And he made me crawl in through a broken window to look for the Camel. I had to smash the glass some more to squeeze in, but I cut my leg. And he wanted me to look for a load of papers. He said he had to have them and I had to find them. Well, they weren’t there, Mog. I knew they wouldn’t be, but I couldn’t tell him that, could I?”

“How did you know they wouldn’t b

e there?”

“What? Well — because — because you took them, didn’t you?”

“Yes,” I said, suddenly realizing, “yes, I suppose I did. But Nick — they’ve gone!”

“Who have?”

“Not who — the papers, I mean.” I was embarrassed. After all Nick’s worries about the safety of Cramplock’s shop, I now had to admit the most important evidence in the whole affair had been taken from there, under my very nose. “They’ve been stolen,” I said rather sheepishly. “And so have —” I bit my lower lip, wondering suddenly whether I should mention my treasure tin. Nick might think it silly and sentimental. “Some other stuff’s disappeared from my room with them,” I said vaguely. “The man from Calcutta must have taken them. He’s probably been in through the wall.”

There was too much information to swap at once and neither of us was really understanding what the other said at this stage. Mrs. Muggerage hadn’t left him a lamp, but she had at least lit the candle; and in the flickering light I watched his face, the remains of his tears still glinting on his cheeks.

“Well,” he said at length, “Coben’s not living there any more, of course, he’s probably in France by now. But my Pa still hit me when I couldn’t find anything, as if it was my fault Coben had gone. He’s so stupid, Mog.”

“I saw Coben,” I said slowly, “at the Three Friends last night.”

Nick’s jaw dropped. “You went there as well?”

I told him about the cab, and the conversation Coben had had with the man they called His Lordship.

“He was nervous, Nick, you could tell. This Lordship must be someone pretty frightening. And Coben was talking to him about —”

I was about to say, about Damyata. But something made me stop. Up to now I’d told Nick everything I’d found out. I had to trust him — I had to trust somebody — it was the only way I could prevent myself going mad. Except that something, deep inside me, was nagging at me to keep it to myself. Just this name. Just for the time being.

Nick was too interested to notice I’d stopped halfway through a sentence. “So where did Coben go after that?” he urged me.

Printer's Devil (9780316167826)

Printer's Devil (9780316167826)