- Home

- Bajoria, Paul

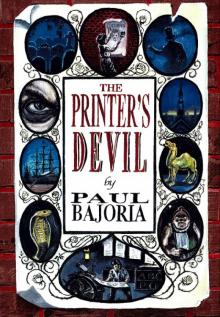

Printer's Devil (9780316167826) Page 3

Printer's Devil (9780316167826) Read online

Page 3

“Shut up,” said Flethick, distinctly and menacingly. He turned to me. His image swam before my eyes. Without moving his lips he said, “You can get out of here, Cramplock’s boy, and if you can pick up the ashes of your bill you’d better take ’em with you.” Despite the slurring of his words I could detect the violence behind them. “You ain’t seen this room, and you ain’t met these gentlemen. You’ve been dreaming. You understand?”

I felt myself nodding. I half believed him. I wouldn’t have been surprised to see him melt away and find myself lying in bed.

“Cos if you remember too much,” Flethick continued, “there’s men in London can help you forget.”

“Ask the bosun nicely,” giggled the laughing man, “and he’ll cut your gizzard!”

“Shut up,” said Flethick again, “you’ve said too much already.” He looked back at me as though I were his worst enemy. He had told me to get out, and I was still standing there. “Off!” he hissed. “And FORGET!”

I stumbled down the stairs, almost falling into the night air, my head thick with the acrid smoke of the little room, my ears buzzing with Flethick’s parting threat. The details of the interview were starting to come to me, as if for the first time. I hadn’t been able to think properly in there: now my lungs filled with colder, cleaner air, and I began to take in what I’d seen. In spite of the men’s lethargic manner, there’d been violence in their words, and I realized I was still trembling with fear of them. Surely they were up to no good? “Such riches!” the indiscreet one had laughed, “the Sun of Calcutta!”

I emerged from the brick archway and blinked at the high, black, damp prison wall in front of me. Still tethered to the lamppost, and scrabbling at the cobbles, Lash was straining to greet me, and when I untied him he practically knocked me over in his evident relief that I’d made it back.

“Am I pleased to see you,” I murmured; and I crouched there for a few moments, letting him lick my face, and tugging affectionately at the little beard under his chin.

A bell somewhere was striking the hour. Eight … nine … ten … eleven. I suddenly felt immensely tired. Glancing up and down the narrow street I saw it was deserted, the only light in sight glowing faintly from the next corner, quite a long way off. The laughing man’s words echoed in my head: “Ask the bosun nicely, and he’ll cut your gizzard!” And I remembered with an uncomfortable crawling sensation just where I was. Despite the painted street sign designating it as Corporation Row, there was another name for this shadowy, high-walled little alley which hugged the perimeters of the prison. Almost everyone who lived around here called it Cut-throat Lane.

I stood up, gathered Lash’s lead so he was tight against my legs, and pulled him after me. You didn’t linger here after dark if you had any sense. As I passed a narrow entrance I heard a cautious whistle like an owl hooting, and knew it for a footpad’s signal to another, the secret language of the filthy youths and children who made their living by being alert when others were tired and careless. Lash growled, and my heart began to beat faster as I thought about the cutthroats who lurked here, about the sinister men in the smoky room, about Cockburn and the prison he’d broken out of, the wall of which was towering forbiddingly to my left. I was hurrying so blindly by the time I got to the corner that I ran straight into someone coming in the other direction.

I nearly cried out, but before I could do so, the other person had melted off into the darkness. Lash was yelping, and straining at the lead in an effort to pursue the shadowy figure, whose footsteps I could hear echoing between the high brick walls as he fled. But I’d seen him, under the street lamp, and had a perfect impression of his startled face stamped on my memory. A tall figure in a heavy black overcoat, out of whose collar rose a dark head, almost bald, the big forehead shining like a dome in the gaslight; he had stark white piercing eyes, a nose curving like a crow’s beak, and beneath it a black mustache which came to a fine point at either side. This was no resident of Clerkenwell! He was in a hurry to get somewhere, it was plain — a foreigner lost in London, looking for someone, or perhaps fleeing from someone. And the look in his eyes, which burned into me even now, after he’d rushed off into the night, bespoke some intrigue as dark and as menacing as the very points of his mustache.

2

INDIAN INK

Tassie came through to the taproom of the Doll’s Head, accompanied by a rich tempting smell, and placed a steaming pie in front of me.

“Now, what do you say to that?” she asked, with a grin so broad I could count her back teeth — and there weren’t very many of them.

“Ta,” I said as best I could with my mouth full.

“The lad would eat all I’ve got if I let him,” Tassie cheerfully announced to the rest of the customers, the usual slightly shabby crowd sitting round the tables enjoying a smoke and a Saturday dinner. “Though I’d say he weren’t lookin’ himself today. Looks like he needs some sleep, woul’ncha say, Mr. Gringle?”

The plump bald man at the bar squinted at me critically, and nodded his suet-like head. “Hollow eyes,” he said meaningfully. “In fact, the lad’s got no flesh on him at all.”

“Wouldn’t think he got more of my hot pies down him than any other body in Clerkenwell,” assented Tassie, wiping her taps.

I looked down at the table, irritated. What business was it of theirs? I was jolly glad I didn’t have flesh on me, if it meant looking like Mr. Gringle, whose belly was at present quivering beneath his filthy and bursting waistcoat only inches from my plate. But Tassie was right to say I needed sleep. After my midnight visit to Flethick’s, I’d spent the rest of the night shifting and bouncing in my lumpy bed, and my fitful bursts of sleep had been troubled by dreams of the most disturbing kind.

In my dream I was blundering around in a kind of haze, like the pungent fog of Flethick’s room, in which people’s faces hovered in and out of sight. Some were friendly, others menacing; but in every case, whenever I tried to speak to them, they would be pulled away from me. One shadowy figure who emerged suddenly from the mist turned out to have the face of the convict from the poster. Another turned out to be the mysterious man with the mustache I’d met in the lane: and as he floated towards me, staring with his stark white eyes, his head had seemed to change into that of a crow, his prominent nose becoming a huge black beak before my very eyes.

To tell the truth, I’d had this dream, or something like it, quite regularly since I was tiny. It was so familiar now that, when it started, I always knew what was going to happen, and I dreaded it so much I often tried to wake myself up so I wouldn’t have to have the dream. The part I always hated the most was when Lash’s barking face appeared, and I reached out to try and hug him, and he drifted away, and I tried to grab his lead to pull him back, but I couldn’t get hold of it, and he barked and barked without making a sound, and he was gone.

The final time, just before I woke up, the dream had been especially vivid. A delicate, shining human figure drifted towards me and I found myself gazing into the beautiful face of my mother, whom I had never seen but whose face I always knew instantly in these dreams, encircled by a headscarf of what seemed to be green and gold silk. She was mouthing silent words in the most earnest, imploring way, as though trying to make me understand something terribly important; but, try as I might, I couldn’t make it out. “Ma!” I called to her, “I can’t hear you! Talk to me! Tell me again!” Her lips continued to move but she was receding now, her eyes alive with urgency, calling out to me silently. Real tears welled in my eyes, from frustration and the pain of parting, as I watched her getting further and further away, still calling …

I shuddered. I didn’t dare say a word to the crowd in the Doll’s Head about last night’s expedition: I knew I’d be laughed at, and besides, it didn’t seem quite so serious now, in the light of the next day, with the spring sun overhead and the street outside full of fruit barrows and shouting boys and animals. And I harbored a nagging fear that, the moment I did say anything, dark force

s would be lurking and waiting to grab me.

But my mother’s apparition haunted me. I was certain that what she had been trying to tell me was in some way connected with last night’s events. My mind worked feverishly all morning, trying to make sense of what I’d seen and heard. Flethick’s friend had been told to shut up when he talked too freely about something called the Sun of Calcutta. “Such riches!” he had chuckled. They had also seemed especially anxious about someone they thought might have been waiting outside. I was convinced that the stranger I’d met in Cut-Throat Lane must be the person they’d been talking about — the one with three friends — and that he had something to do with the Sun of Calcutta, whatever that was.

Gringle took a sip of his beer, and went over to sit down with some cronies, coughing loudly as he went. I thought it might now be safe to ask Tassie something.

“Tassie,” I said, in a low voice, “where’s Calcutta?”

“Where’s Calcutta?” she echoed loudly, and I winced as her voice pierced the hubbub of the taproom. “Well, er — it’s a foreign place, Maaster Mog.”

“I know it’s a foreign place,” I said, “but where is it?”

Her mouth worked for a couple of seconds with no sound coming out. “Well, er — it’s — a long way off,” she said, and it was obvious she hadn’t a clue. “It’s in, er — the South Pole.” And she seemed satisfied with this sudden piece of inspiration — triumphant, even.

“What are people like there?” I asked her, through a mouthful of pie.

“What are they like?” She echoed again. “Why, they’re — different,” she blustered.

“How, different?”

“Well, they, er. They.” She wiped her taps furiously, as though they were crystal balls and might supply her with the answer. “They probably look like sheep, with curly horns. But I ain’t never seen anyone from there, so I can only say what I’ve heard.”

I decided Tassie was no use at all when it came to geography. But things started to look up almost immediately with the arrival in the inn of Bob Smitchin, a cheerful youth well known in these parts of town. There wasn’t much that went on that he didn’t know about. He always had a winning word for everyone, and usually something extraordinary to sell — which people were better disposed to buy after he’d been nice to them.

“Hello, Mr. Gringle! Mr. Ratchet! Another warm one, eh? Hello, Tom, get the bricks all right? Mornin’, Mr. Fettle. Dot, my love, how was that bacon?Mornin’, Charlie, still on top?” Indeed, wherever he went there were so many people he knew that it was a wonder he ever got anything done at all: he could have spent his entire life greeting people. Once he’d worked his way through the taproom, exchanging handshakes and pleasantries, he came to lean against the bar close to where I was sitting.

“Mog!” he said, noticing me. “The printer’s devil, large as life!” He knelt down to make a fuss of Lash, who sniffed and licked at his fingers happily. “You look like you’ve got something worryin’ you,” said Bob, standing up again. “Nothing amiss, is there? Nobody ill?”

“No, Bob,” I said, “just a bit tired. I was working on posters till late last night.”

“Posters! Not that escaped convict?” he said, giving money to Tassie in return for a full pot of frothy beer she’d just plonked on the counter. “That’s a great job you done on them posters. I seen them up on doors and walls in I don’t know how many places today. What a villain! Murderous! Eh?” He gave a whistle, and then a bright smile.

“I was sick enough of seeing his face after I’d done a hundred of ’em, I can tell you,” I said.

“I’ll bet you was,” he replied, putting the beer to his lips. “Aaah!” he said, after taking a sip. “Tassie’s finest, just the thing to lay the dust.” A slight wince creased his face as the aftertaste hit him. He’d acquired a white mustache from the foam on the beer, and he wiped it away with a stained shirt cuff. “Yeh, that convict poster,” he continued, “what fine big letters, Mog, big bold ones. Not that I knows what they say, but I can tell sure enough they’re big bold words fit to make any citizen watch their step where convicts is concerned. And what a face! What a fine murderous convict’s face to stick up around town. Eh? Only thing is —”

He took another draught of beer, and acquired another frothy mustache in the process. “Only thing is, Mog,” he said again, “I seen that face before.”

“What do you mean, seen it before?” I asked, intrigued. Was he about to tell me he knew where the escaped convict was?

“On another poster. I mean, it’s a fine face, for a villain that is, a fine murderous convict’s face to frighten anyone what lays eyes on it. But it’s the same face what was on another poster for an escaped convict a month or two back.”

I stared at him. “What, exactly the same?” I said.

“No two ways about it, my son,” Bob said cheerily. “Never forgets a fiz, doesn’t Bob, and that one I seen before. Same eyes, same crooked stare. Same big square chin.”

“Well, maybe he’s escaped twice,” I said, “maybe they caught him the first time and locked him up again, and he’s just escaped again.”

Bob shrugged. “Maybe he has,” he said. “Except I feel sure it ain’t more than a fortnight since he did a bit of dancin’ on thin air. The old Paddington frisk? Eh?” He made a strange jerky movement with his body and stuck his tongue out.

I was looking at him blankly.

“They hanged him,” he explained.

“What?” I said, worried now.

“I could have sworn I heard tell,” he said, “that the convict on the other poster was caught and hanged. I could have sworn old Tommy Cacklecross the prison gatekeeper told me that. And if he was hanged, well, they wouldn’t be putting out posters of him saying he’s on the loose, would they? Before you go back and face Cramplock,” he said, leaning closer as if to impart a confidence, “it might be worth you going and having a word with old Tommy, see if he knows the face. He’ll put you right.” And he stood up again, beaming, looking around for someone else to talk to.

“Well, thanks for the advice,” I said crossly. Who was Bob to come criticizing my handiwork, telling me I’d put the wrong face on the poster? If there was anything wrong with Bob it was his habit of putting his oar in where it wasn’t wanted, reckoning he knew more about other people’s jobs than they did themselves. But an uncomfortable dread nagged at me: might I have used the wrong picture? One big ink-covered engraving could look remarkably like another as we fitted them into the blocks in the shop. And Bob’s memory for faces was usually impeccable. What on earth would Cramplock do if it turned out I’d misprinted the poster a hundred times over?

As I ate the rest of my pie I tried to work out where I’d live and what I’d do if I lost my job, and how I’d find enough food to give Lash — and I’d soon constructed an entirely plausible future which saw me sleeping on the cobbles beside the Priory gatehouse covered up in waste-paper I’d stolen from Cramplock’s garbage cans — until suddenly the word “Calcutta” woke me up.

“Yes, Maaster Mog’s quite the mysterious one this morning, ain’t you Maaster Mog?” Tassie was leaning over her bar, chatting to the effusive Bob. “Asking me all sorts of questions about Calcutta and the South Pole, you’d think I was a schoolmaster to be inquired of!”

“Questions about Calcutta?” queried Bob. “Why, that’s a funny thing, Mog, because that’s exactly where this came from.” And he produced from his inside pocket a very large silk handkerchief in an exotic pink and orange pattern, with gold thread running in an ornate trace around the edge. “Thought I might find a likely buyer for this,” he said. “Keep me in beer for the evenin’. Eh?”

“That came from Calcutta?” I asked, intrigued.

“Off an East Indiaman who came home last night,” Bob replied, “straight from the Orient, full of riches to dazzle the worldliest of us! And I can offer this little square of the mystic East —“ he was getting into his stride and waving the handkerchief around at the

amused crowd, ”— silk of a quality you never seen, for a song, to the highest bidder. Direct from the hold of the Sun of Calcutta, and unloaded not two hours since. Picture this fine silk softly stroking the neck of a Maharaja’s beautiful daughter.” He put it to his nostrils. “Mmmm! Still richly scented with her heavenly perfume!” There was a ripple of interest among the other customers. He was good at this. “And now, here it is,” he continued, “available to anyone with the wherewithal, to adorn themselves like a true princess!”

But I wasn’t listening to Bob’s eloquent salesmanship. I’d latched onto one specific part of his patter, and I wanted to know more. “The Sun of Calcutta,” I said, “it’s a ship, then, is it?”

“She certainly is, and a finer one you won’t find in the whole port of London,” Bob enthused. “Laden with the gifts of the Orient!”

“Where is it? Where can I find it?”

“Where can you find it?” he repeated. “Where can you find it?” He turned to the little crowd and waved a hand towards me, inviting them to share the joke. “He wants to know where he can find the Sun of Calcutta!” he said, and laughed aloud. “Where d’you find any new-returned East Indiaman, young Mog? In the dock, that’s where — and I don’t mean the kind of dock your escaped convict makes it his habit to stand in!”

Clattering and screeching like the noise of hell itself, the wheels of a hundred carts and carriages mingling with shouting voices and the screaming of wheeling seagulls filled the hot air above the London docks. I fought my way along the riverside, holding tight to Lash’s lead; dodging horses’ hooves, avoiding persistent costermongers trying to get me to buy fruit from their untidily laden barrows; and pushing with difficulty between the heavy coats of gentlemen and tradesmen who thronged the dirty streets. The heat was almost unbearable, the horses whinnying in frustration at the crush. Everyone was sweating. The further I went, the more like a foreign country it seemed, with sailors from overseas laughing and gathering in the doorways of inns and shops, Jewish men in black coats and hats, men carrying things and shouting at the crowd to part and let them through, everyone babbling in foreign languages, arguing and fighting with one another. Every now and again I stopped to ask someone if they knew where I might find the Sun of Calcutta; and every time, if they knew at all, they’d point me further east, towards Wapping and Shadwell.

Printer's Devil (9780316167826)

Printer's Devil (9780316167826)