- Home

- Bajoria, Paul

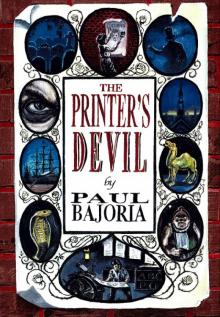

Printer's Devil (9780316167826) Page 9

Printer's Devil (9780316167826) Read online

Page 9

“When you’ve done that,” Cramplock said, “you can pull a hundred of these.”

He’d set up the type for another elaborate poster; and after he’d disappeared into the back room to do some accounts I went over to have a look. Even without taking a copy I could make out what it said. It had type of several different sizes, and an engraving which seemed to be of some sort of animal.

EXHIBITING FOR ONE MONTH ONLY AT

MR. HARDWICKE’S

at BAGNIGGE WELLS

the Most REMARKABLE CURIOSITY

that Ever was Seen!

CAMILLA

the PRESCIENT ASS

The only BEAST in the WORLD guaranteed to tell FORTUNES and Prophesize EVENTS with Perfect Accuracy also to Read Cards, Interpret Horoscopes and FORETELL INHERITANCES OF WEALTH This EXTRAORDINARY CREATURE is to he Displa’d DAILY and will perform Demonstrations at the Hours of 11, 12, 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5 o’Clock Admission on payment of One Shilling

The engraving was of an absurd-looking creature with two large ears, and a person standing next to it holding up his hands in what was meant to be astonishment.

Laughing, I reached for some scrap sheets of paper to make a couple of test copies, to make sure the poster was properly laid out.

“Do you suppose this ass really can tell fortunes, Mr. Cramplock?” I ventured to ask, pulling out one of the tests and examining it.

Cramplock grunted. “Not if Hardwicke’s got anything to do with it,” he said. “Biggest swindler in London. The poor fools who flock to see it will probably find it’s an ass standing in front of a curtain, with his wife hiding behind the curtain shouting out.”

I printed off five or six more and looked them up and down with admiration.

“Did you give my bill to Flethick?” Cramplock suddenly asked.

I froze.

“Ah, Yes,” I said.

“Good. That’s all right then. He owes me plenty, and it’s high time he settled his account. The number of things —“

“But,” I butted in, “he didn’t give much impression that he’d pay.”

Cramplock looked at me intently and rubbed his cheekbone. “Why? What did he say?”

“He, er — he told me to tell you he wanted no bill, Mr. Cramplock,” I said, my face going bright red with embarrassment again, “and he, ah — burnt it up.”

The little man’s eyes nearly fell out of his head, and would have done if his glasses hadn’t stopped them. “He what?”

“Erm — burnt it up,” I said, starting to wish I’d never told him. He still showed no sign of understanding. “Burnt it,” I repeated helpfully, trying to smile. “Up.”

Cramplock made a noise like a chicken. “But — but — but — why did you let him?”

“I didn’t have much choice,” I said. “He’s not a nice man, Mr. Cramplock. There were lots of his friends there. He was behaving very strangely.”

“He’ll behave more strangely when I get my hands on him,” squawked Cramplock. “Burning my bills! Who does he think he is?” He wasn’t just cross now, he was enraged. He pushed me out of the way of the press and started printing the rest of the posters himself, working the machinery furiously and almost throwing the ink at the roller. For the next ten minutes he carried on muttering to himself, occasionally slamming things down on the table. I sat picking at the type in the cases, not daring to say any more.

After a while he addressed me again. “By the way,” he said, “that poster you did.” He still sounded annoyed.

“The convict?” I said, wondering what was wrong.

“Yes, the convict. A man from the jail came to see me yesterday. It seems you made a bit of a mistake with the picture.”

A horrible dread crept over me. “What mistake?” I asked, quietly.

“You printed the wrong face,” Cramplock said, irritably. “The wrong engraving. That wasn’t the fellow at all. That was some other convict from months back.”

So Bob Smitchin had been right. But I felt sure that was the engraving Cramplock himself had given me to print — so it was his mistake, not mine, though I couldn’t possibly say that to him in his present mood.

“Made me feel quite a fool, the fellow did,” Cramplock was continuing. “How can you expect to catch a criminal when you put out a poster with somebody else’s face on? He must be laughing like a jackass, wherever he is.” He flung an inky old rag at me. “And more to the point, the jail won’t pay!” he shouted, getting more and more angry. “Because we got it wrong! Call yourself a prentice? Well, if I get no money for the posters you get no wages this week, and that’s that.”

“But—” I said.

“Don’t give me any sob stories, Mog Winter. First you disappear for nearly a whole working day without any explanation. Then I trust you to run a simple errand and you come back from Flethick’s with nothing but a pathetic tale about how he burnt his bill — fact is you probably lost the bill before you even got there. Don’t argue, Mog! And then to cap it all you print a hundred pictures which are meant to be a man called Coben only the face ain’t a man called Coben, it’s some other fellow who was hanged months ago. It’s no good you looking like that, Mog; whether you’ve been sick or not you won’t get any sympathy today.”

I must have gone as white as a sheet. I felt as though a knife had hit me in the back.

“Did you say C-Coben?” I stuttered. “What on earth makes you say Coben?”

“Because that was the name of the escaped convict, as you well know,” Cramplock said.

“His name was Cockburn,” I protested.

Cramplock wheeled. “Don’t you know anything, Mog Winter? It’s pronounced Coben. It might look like Cockburn, but you pronounce it Coben, as a rule. So now you know. And you can get that sick look off your face, because I’m not changing my mind about your wages!”

6

CAMEL-HUNTING

The dirty sky was full of pigeons as I left the shop and ran through the streets and lanes. I just had to talk to Nick. The afternoon had passed interminably, with Cramplock in a foul mood and my head so full of my recent adventures I couldn’t concentrate on the job in hand. Because I’d been late, he’d made me stay behind for hours. But how was I supposed to concentrate at a time like this?

At last he’d let me go, with very little daylight left, and within minutes I was tiptoeing into the forlorn little yard at Lion’s Mane Court, keeping a beady eye open for observers. I had deliberately left Lash behind tonight. Mrs. Muggerage now knew what he looked like, and following our near-miss with the cleaver the other day she was on the lookout for a boy with a dog. This way, I thought, I’d be less conspicuous. I really didn’t fancy running into her, or the bosun for that matter; and I pressed myself against the stable wall pretty rapidly when I heard both their voices floating down from above. Well — floating is the wrong word, really, their voices being more the plummeting sort. When Mrs. Muggerage spoke it was like a man playing a concerto on an anvil.

I peered round the corner and could see them both up there on the balcony. I think the bosun was drunk, because he was laughing uncontrollably and he had nothing on over his vest. For the first time, I sized him up.

He was huge. His skin was grimy, and there was almost no hair on his bulky great head. He was badly shaven, the lower part of his face almost black with short bristles; and black hairs spilled out of the holes in his string vest, as though he were really a gorilla posing as a bosun, and I’d caught him out of costume. I had little doubt, either, that with his great broad arms and unshakable bulk he could have taken on most gorillas in a hand-to-hand fight, and won. With both of them up on the little wooden balcony, I wondered how it remained attached to the house.

“Ha ha ha ha,” the bosun was bellowing, “Mrs. Muggerage you’ll be the death o’ me, ha ha ha ha!”

“With a bit of luck,” I murmured to myself, pulling my head back round the corner. Nick had said the gruesome pair usually went out at night — how long might I h

ave to wait before the coast was clear?

“There’s hot puddin” ’ere waitin’ for ya,” came Mrs. Muggerage’s voice, “you naughty boy! Come and sink yer teeth into this, it’ll keep yer out o’ mischief!” And there was more laughing from both of them. I couldn’t resist another peep round the corner, and there they were on the balcony, the bosun and Mrs. Muggerage, clasping one another as best they could in an amorous embrace, like a pair of prize bulls with their horns locked.

I shuddered, and decided to lie low in the stable until it grew dark. The horses shifted uneasily as I pushed open the wooden half-door and slipped inside. Usually, when someone came in, I suppose they knew it meant they were about to be ill-treated or put through some punishing job of work.

“Shh … it’s only me,” I whispered, patting their flanks, and the sick one coughed violently in reply. There was no one over in the corner today, just an upturned wooden box where the old tramp had been slumped last time, against an especially damp patch in the stable wall. As I sat down there, I noticed a little knothole in one of the planks of the wall. When I pressed my eye to it, I found I had a perfect view of the door of the house and the balcony, and of the bosun and Mrs. Muggerage still sitting up there, their voices echoing round the yard. Inspecting the wooden plank more closely, I could see that it wasn’t a knot in the wood at all, but a hole crudely and quite deliberately cut. So someone had been watching! Evidently this was what Coben and Jiggs had meant in their note, when they’d written

Eys ar watchin you now.

Still, it was ideal for me, I reflected. I could keep track of the bulky twosome’s every move, without anyone having a clue I was here — so long as whoever was more accustomed to sitting here didn’t come back and find me.

I hunted about for any other clues I might find: anything dropped in the hay, or scratched on the planks of the wall. There seemed to be nothing of any significance — until I lifted up the box, beneath which I found a little book lying among the dirty straw. Whoever had sat here had been reading, perhaps to relieve the boredom of keeping watch for hours on end. It was a flimsy little volume, badly sewn together, with about twenty-four pages; the edges of the paper were ragged, and the sheets seemed to be of slightly different sizes, so they didn’t quite fit snugly together when the book was closed. If I’d produced such a thing for Mr. Cramplock he’d have given me a thick ear. Holding it up to the light I noticed, every few pages, the same watermark cropping up that I’d seen on the customs document the other evening—a sleeping dog, with its tail curled around to touch its own nose.

It was a poem. Now, I’d come across a fair amount of poetry, because we were quite often printing poems and ballads in the shop; but I’d never seen a poem quite like this one before. It seemed to be a kind of riddle, but try as I might I couldn’t make much sense of it.

Gilded, like a tigress in the light

Of evening on the Brahmaputra plain,

Whose sudden motion puts the foes to flight

That trespass on the heart of her domain,

I prowl, with an inimical delight

In ruin, and in chaos, and in pain;

I slink, and shift my shape before the night

Makes black and gold and white all once again.

The moment I am seen, I disappear,

And smile at the confusion I can spread;

My power will outlast eternity.

I lift my subtle nose to smell the fear,

And settle down, inhabiting your head,

Confounding your attempts to fathom me.

This was as much as I’d read before I felt my eyelids growing heavy and my mind sinking eagerly into a beckoning sleep.

But I had to be on my guard in case the bosun came by, or in case the old tramp came back. I tried to wake myself up, by putting down the book, taking another glance through the peephole, taking a few deep breaths. But try as I might, I still couldn’t rid myself of the urge just to close my eyes and drop off, leaning against this stable wall.

And then suddenly a noise from outside made me sit up. Through the peephole I could see the bosun coming down the front steps. The daylight was fading fast and he was just a grey collection of moving patches in the dusk, but it was unmistakeably him; and he was off out somewhere. I saw him stop in the middle of the yard and look purposefully about him, as though trying to detect any unwanted eyes. I half-feared that mine, peeping from the split plank in the stable side, might radiate some sort of visible glow and give me away. But after a few moments’ pause, he walked off. I think he’d heard the coughing of the horse, and had stood listening just to make sure it wasn’t the coughing of a person.

Although, as far as I knew, Mrs. Muggerage was still in the house, the yard was so still and dark that I decided to take my chance. Perhaps I could attract Nick’s attention without disturbing her. But as I tiptoed over to the scullery, where the trapdoor led into the cellar, I could hear a distinct sound of snoring from behind the pink door: a deep, throaty grunting noise, more like a pig than a person. There was no point in trying to get in this way.

I ran across the yard to the grille above the cellar window; but I could neither hear nor see anything down there.

“Nick!” I hissed softly.

Nothing.

“Nick!” I whispered again. “Are you there?”

I didn’t dare call any louder. I lifted my head and took a quick look around, in case the bosun should be coming back; but there was no sound.

I took hold of the grille and, almost in desperation, gave it a tug. To my alarm, there was a loud scraping sound as plaster fell from the wall, a brick sprang out, and the whole grille came away in my hands. I closed my eyes in despair. If this hadn’t woken Mrs. Muggerage it would be a miracle! I crouched there, not daring to let go of the grille or lift it further, in case it made more noise.

There was a scratching sound from the cellar and I heard the window creak open beneath me. I froze.

“Who’s that?” came a bold voice. It was so positive in the fragile silence I almost ran for my life, until I realized it was Nick.

“Ssshh!” I whispered, “it’s me — Mog!”

“Mog! What are you doing here? If Ma Muggerage finds you …”

“I’ve got something to tell you.”

“Well you can’t get in. You better go.”

“Can you get out?”

There was a pause. “Hang on,” he said.

Nick was an old hand at slithering through gaps, and the hole I’d made by pulling the old grille loose was just big enough. Within a minute or so he was standing next to me in the darkness, brushing himself off.

“Wait,” he whispered. Holding one hand against my ribcage to signal me to stay back, he moved through the dark courtyard, his eyes far more alert to unusual noises or movements than I could have been. Furtively, peering round each dark corner before venturing round it, he led me out through a low passage towards the more lively yard of the Lion’s Mane Inn, where there were lights, and people leading horses by the reins, and calling out to one another. He pulled me back suddenly against a damp wall as a small group of men walked past.

“Not your Pa,” I said, fearful.

“No — but men who know him well enough. And know me.”

I could see Nick now, in the light coming from the inn. He was wearing the same clothes as yesterday; but with a shock I noticed that tonight he had an enormous bruise on his forehead which hadn’t been there before.

“Nick!” I exclaimed. “Where did you get that?’

He grinned tiredly. “Look good and shiny, does it? It feels pretty big I must say. Ma Muggerage gave it me this morning while you were running off. I think she got a decent look at you, you know. If she finds you round here again she’ll kill you.”

“Does it hurt?”

“It did before. Can’t feel much now.” He looked at me. “It’s in the same place as yours.”

I reached up to make sure my bandage was still stuck on. Cautiously, he

pulled me back into the shadows against the wall again. “Listen,” I said, deciding not to waste time, “Coben’s a murderer. He’s just escaped from prison. I found out today.”

“How do you know?”

I told him the story of the Cockburn poster.

“Lots of ’em about,” said Nick, sounding grimly grown-up all of a sudden. “Murderers, I mean. My Pa knows plenty of them, and I wouldn’t wager against his having a few murders to his own name down the years.”

There was silence while I contemplated this. I could easily imagine the powerful bosun murdering someone … crushing the life out of them, or strangling them with a length of rope…. The images which came to mind were so vivid my knees began to knock together.

“Has he still got the camel?” I asked.

“Far as I know”

“Well, I think we should shift it,” I said.

“Shift it where?”

“Anywhere. You know that tramp I said was in the stable this morning? He must have been spying for Coben and Jiggs. There’s a little stool there and a peep hole where somebody’s been watching this house pretty often, I reckon. They know that camel’s here, Nick, and they’ll try and get it, I know they will.”

“Well, that’s why Pa left Ma Muggerage on guard,” said Nick, in a tone of voice that suggested I was being stupid not to have realized that myself. “Pa’s getting scared. I heard them talking this afternoon. He won’t have the place left empty. It was that note put the wind up him, the one about the eyes.”

“Well, there are eyes,” I said. “Somebody’s going to kill somebody to get that camel.”

Printer's Devil (9780316167826)

Printer's Devil (9780316167826)